Phil Nuttridge continues his series of articles looking at the modern take on diet and nutrition. He explodes many of the dietary myths that defined the latter decades of the twentieth century and left their legacy of chronic illnesses in the first decades of this century. In this month’s article he looks at supplements and shares some thoughts on why it might be beneficial to take them. More information can be found on Phil’s website cuttingcarbs.co.uk or by following him on Instagram: CuttingCarbsUK

He took a bottle from his pocket and shook from it a tablet about the size of one of his fingernails.

“That” he announced “is a square meal in a condensed form.……..It contains soup, fish, roast meat, salad, apple dumplings, ice cream and chocolate drops, all boiled down to this small size, so it can be conveniently carried and swallowed when you are hungry and need a square meal”

From The Patchwork Girl of Oz

Eating pills instead of food was the stuff of science fiction when I was a boy. You could not boldly go anywhere in the Universe without your nutritious pills. Today, if you survey the shelves of supplement pills in any health-food store or supermarket you might be forgiven for thinking that day is virtually upon us. But what of the reality of supplement pills? Does a pill a day (or indeed, multiple pills a day) keep the ailments away?

Firstly, let me pin-down the chemicals those supplement pills are offering us. In a very simplistic model there are two key components of our diet: Macro-nutrients and micro-nutrients. The macro-nutrients are the carbohydrates, fats and proteins that should form the bulk part of the food you eat; fats and proteins are essential macro-nutrients and must be part of your diet. Whilst we do not normally consider any of these as worthy of supplementation, some people do. Body builders for example use protein supplements to (supposedly) enhance muscle repair and many of us take fish oil (fat) supplements to boost the essential omega 3 fatty acids.

Micro-nutrients are then the chemicals needed by your body but in much smaller quantities. Traditionally this group is sub-divided into vitamins and ‘minerals’ although as you will see I will use the more accurate label ‘essential elements’ for this latter group. In all there are thirteen identified vitamins, each of them an organic compound vital for the body to function – A, D, E and K are the fat soluble vitamins; the B group and vitamin C are the water soluble ones. Some vitamins can be made in the body (for example vitamin D can be synthesised in the skin from sunlight and cholesterol) but for most people, these thirteen vitamins need to be part of the diet either through food or supplements.

Macronutrients and vitamins give our bodies the elements of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and nitrogen. In addition there are other elements essential for body function: Calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium and phosphorous are the primary essential elements; iron, zinc, manganese, copper, molybdenum, iodine, chromium and selenium are further elements needed by the body but in much smaller ‘trace’ amounts. Traditionally this would all be grouped as the ‘minerals’ but in the strict chemical definition of this term, not all the elements listed above are actually minerals. These essential elements and trace elements, like vitamins, have to be part of our diets either through food or supplements.

When we think of supplements we are usually referring to these vitamins and essential elements. Additionally, there are a number of supplements that people might take that do not neatly fit into this classification.

Examples of these ‘other’ supplements are:

- probiotics which are supplements taken to supercharge your gut biome

- fibre supplements (a form of indigestible carbohydrate)

- food substances that might not otherwise be part of your diet that have health benefits. Apple cider vinegar, co-enzyme Q10 and turmeric are examples of these. I have also previously mentioned protein and omega 3 supplements as further examples.

My primary focus in this article will be the vitamin and essential element supplements but I will touch on some of these other supplements as part of that journey too. I shall devote an entire article (entitled ‘Not a fibre of truth’) to fibre, as that is a very interesting story in its own right.

OK, so we have now met the key players in this story of supplements. But let us step back a moment: Human physiology has little changed over the millions of years that hominids have been around. We have survived without pills for most of that time so why on Earth would we need them now?

That is a good question but one I can very easily deflect. Essentially, we have lost our way with nutrition: We no longer eat what we used to and we no longer eat in the way we used to. And although some of the foods we eat today may resemble what we might have eaten in our distant past, those foods are but a shadow of what they used to be in terms of their nutrient content.

Did you know, for example, that strawberries from fifty years ago are estimated to have had twice the vitamin C content of modern-day strawberries. Supermarket-bought strawberries, forced to grow out of season, hybridised for their sweetness (rather than their nutrient content), shipped half way around the world and sprayed to keep their appearance, have even less.

When we were ‘gatherers’ (as part of our hunter-gatherer past) the things we scavenged were predominantly leafy green vegetables – fruits were rare and very seasonal in our bleak northern European habitat of old. When meat was scarce, it is hypothesised that we probably gathered over 170 different species of leafy green vegetable to ‘supplement’ our diet. Nowadays we eat fewer than twenty species of leaves. And as with the fate of modern strawberries, the leaves we do still eat are excessively hybridised, grown out of season and on poorly nourished soils, all factors that deplete their nutrient content compared to varieties in our ancient past.

Our modern-day sweet tooth also means we are drawn to the wrong sorts of vegetables – the starchy root, grain and cereal crops all of which bring lots of carbs and calories to the table but alas very few of those essential nutrients we need.

When it comes to meat, things fare little better. Because we have been led down the wrong path of ‘fat is bad’, most modern cuts of meat we now eat lack the marbling of fat that brings flavour but more importantly brings the fat soluble vitamins A, D, E and K. The pressure to produce cheap food has led to some very unhealthy practices regarding the way we raise meat. Ruminants fed on soy, grains and cereals are not only harmful to the environment but also their meat contains far fewer nutrients (for example) omega 3 fatty acids than ruminant-meat raised on grass as Nature intended. We also now shun the organ meats and yet these were staples for our parents and grandparents. Did you know liver is the most micro-nutrient dense food there is? Bar none. It even contains vitamin C and in a form that is more heat stable than in fruit.

So as you can see we have rather lost our way with regard the food we eat and its nutrient content. You will often hear people say “If you have a balanced, healthy diet then you do not need to take supplements”. In an absolute sense that would be true if we all did indeed have a nutritionally fulfilling human diet, but most people’s diets nowadays are neither balanced nor healthy. We have disconnected from the foods that made us human.

For me there are five circumstances when you should consider taking supplements. You should think seriously about supplementation if:

- You rely on supermarkets for your food.

- You are on a restriction diet – for example, if you have chosen to exclude a food group such as meat or dairy from your diet.

- You are on prescribed medication.

- You have a diet high in ‘anti-nutrients’.

- You are seeking a health outcome that can be improved with high dosage of key micronutrients.

I shall look at each of these circumstances in a little more detail. Lest you think that I am nothing more than a pill-pusher, at the end of this article I shall show you how by incorporating a few traditional foods into our diet (actually, put them back in our diet) we can get many of the missing nutrients once more onto our plates without recourse to pills. Not everything needs to be solved by taking a pill.

- You rely on supermarkets for your food.

As I have already described, the nutrient load of many of the foods we eat nowadays is far less than it used to be. Intense mono-crop agriculture that depletes soil resources, the need for new hybrids of crops for fast growing, disease resistance, enhanced flavour and longer shelf-life are all to the detriment of the level of nutrients contained within those foods. Plant foods are grown for profit margin, not the goodness they deliver.

Yes, if you grow your own vegetables with good soil management, then you can overcome much of this. If you insist on meat with good provenance, organically raised and grass fed, then you will have highly nutritious meat. But if you can only source your vegetables and meat from supermarkets, then you may well find yourself low on certain key nutrients making supplementation beneficial.

The tendency of many to over-eat is probably in part due of this diminished nutrient density of your food. Our bodies are innately programmed to seek nutrition – the vitamins and essential elements needed by our bodies. But if the food we eat is not providing enough of these key nutrients, then the body will continually make us feel hungry encouraging us to seek more food to supply that shortfall in nutrients. You will want to eat twice as many modern-day strawberries to get all that vitamin C you need. Whilst that over-eating may well top-up the missing nutrients, it will over-load our bodies with surplus calories and in the case of those strawberries, too much of public enemy number one: Sugar. Our desire to over-eat can therefore be a measure of our programmed need for nutrients being poorly met by supermarket-bought food. Never before have we been so over-fed yet under-nourished!

2. You are on a restriction diet

Our omnivorous evolution means that we have metabolic adaptations to eating both animal products and some plant products. But the key thing about being an omnivore is that we should eat both animal and plant foods.

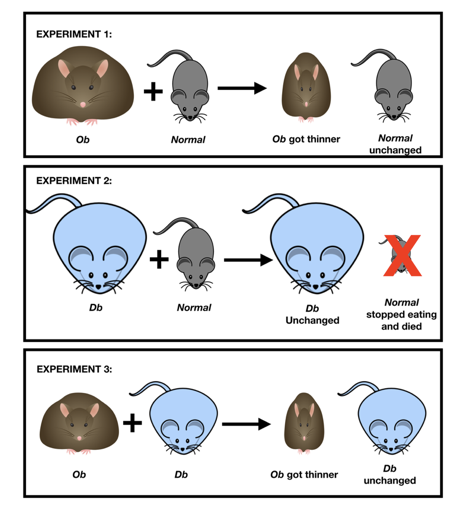

There is a somewhat disturbing plant-based fad at the moment, its followers cutting all meat products from their diet on the basis of health and for the environment. Whilst my analysis of how properly raised meat is in fact good for the environment is beyond the scope of this article, allow me to dispel a few myths regarding a meat-free diet and good nutrition.

We will often hear how “carrots are full of vitamin A”, or “mushrooms (left out in the sun) are full of vitamin D” or “spinach is full or iron”. Alas, this is misleading. Yes, in the laboratory, that vitamin A, vitamin D and iron can be extracted into a test tube from those plant foods. Unfortunately our human bodies cannot do the same. The vitamin A that humans need is in the form of retinol but the form in carrots is carotene. Many of us cannot process carotene and even those of us who can are only able to access a meagre proportion of it. Meat, particularly liver, contains retinol aplenty. You would have to be continually munching on many kilograms of carrots to get the vitamin A load of just 100g of calves’ liver.

To get the recommended daily dose of vitamin D you would need to eat 3kg of mushrooms every day but even then it would be in a form called D2; humans need the D3 form. Just one teaspoon of cod liver oil would give you three and a half times your daily requirement of this vitamin and in the right form. All that mushroom munching would be in vain.

The iron in spinach is a form termed non-haem; humans however need the haem form found in red meat. I assure you, Popeye did not get his muscles from eating spinach.

So if you are choosing to eliminate animal products from your diet, the list of vitamins and essential elements you will be deficient in, and should therefore consider supplementing, include:

- Vitamin A in the retinol form (plants have the wrong form)

- Vitamin B6 from liver, tuna, salmon (the plant forms are very poorly absorbed)

- Vitamin B12 (there are no plant sources of this vitamin)

- Vitamin D3 (plants contain D2)

- Vitamin K2 (plants contain K1)

- Omega 3 fatty acids from fish oil (all plant sources of omega 3 are also higher in omega 6 oils which are inflammatory)

- Haem iron (all plant sources are non-haem iron).

3. You are on prescribed medication.

Most prescribed medications have side-effects. Some of these side effects are little more than inconvenient but some are rather more serious. In a number of cases, an appropriate intake of supplements can mitigate some of these side-effects. For example, statins are a drug prescribed to lower cholesterol although you should read my previous article if you are under any illusion that this is a good idea. The way statins do this is to interfere with the chemical pathway in the liver that produces cholesterol. Unfortunately, this same chemical pathway also produces other useful chemicals for the body, one of those being co-enzyme Q10. Statins interfere with the body’s ability to make this vital chemical and so supplementation with CoQ10 is essential for those taking statins.

4. You have a diet high in ‘anti-nutrients’.

The subject of ‘anti-nutrients’ is a growing area in nutrition research and one I shall address in a future article (entitled: “Vegetables ARE out to get you”). Essentially plants do not want to be eaten – who does – but unlike animals they cannot fight or run away. Instead plants engage in chemical warfare. A whole range of ‘anti-nutrients’ have developed in the leaves, husks and fruits of plants that intentionally harm any animal or insect that may eat them, making the plants less likely to be eaten again. For example, soy and flax contain phyto-oestrogens whose main evolved purpose seems to be to make insects that eat them sterile. A perfect strategy if you want to avoid being eaten by insects!

Research is showing that plants have evolved a myriad of chemicals with the same end objective of reducing their chances of being eaten. Many of these chemicals are in the plants we humans eat. For example, if you eat a diet high in spinach, kale, asparagus and rhubarb you will expose yourself to oxalates. These chemicals interfere with your calcium metabolism, producing crystals in the body where they should not be, for example in the joints (gout), in the kidney (kidney stones) or in the gall bladder (bile stones). Supplementing with magnesiums citrate can mitigate some of these effects as can taking calcium supplements. This latter strategy does not necessitate taking pills as you could of course just make sure you have a good source of calcium in the same meal as the oxalate containing vegetables: Have some feta with your spinach, have some cream with your rhubarb!

5. You are seeking a health outcome that can be improved with high dosage of key micronutrients.

Vitamin C is a great way to battle colds. Some nutritional therapists advocate up to 1000mg of Vitamin C every hour at the first onset of symptoms to help your body battle the cold lurgy. Yes, you read that correctly – 1000mg every hour. (You stop taking the hourly dose of vitamin C once the symptoms subside or you start running to the toilet, a sign that your body no longer needs the excess vitamin). This is way above the recommended daily intake of vitamin C of just a few hundred milligrams per day but that recommendation is merely enough to stop you getting scurvy. The high dosage being advocated here is that to achieve a significant ‘other’ health outcome.

There is no way you could consume enough fruit to achieve 1000mg of Vitamin C every hour and nor would I recommend it even if you could, as that much fruit would over-load your body with sugar and that would be far more harmful. So this is a good instance when supplementation would be of value. Interestingly, animal liver is an under-valued source of vitamin C. Whilst cooking liver reduces the bioavailability a little, meat-sourced vitamin C has the huge advantage it is not accompanied with sugar. This is important as the vitamin C molecule is very similar in shape to the glucose molecule and so if you eat a lot of sugar with your vitamin C, that glucose competes with the vitamin C diminishing its absorption and utilisation.

Vitamin C is not the only natural supplement that should be in our medicine cabinet – vitamin D taken in amounts well over and above the recommended daily intake is a great way to boost your immune system. High dosages of magnesium can help with muscular aches and pains and reduce the incidence of muscular cramps. Omega 3 fatty acids are part of the body’s natural mechanism to reduce inflammation and so those with high levels of systemic inflammation will benefit from a supplement high in omega 3 but crucially, also low in pro-inflammatory omega 6s.

Having just surveyed the circumstances where supplementation might be advantageous, in what form should you take these supplements? Yes, you could dive into those shelves at the supermarket to buy the missing nutrients in pill form, but the more robust strategy is to put foods into your diet that naturally deliver those missing nutrients. The food form of any nutrient is always best.

Fresh, locally-sourced and (particularly for plant foods) seasonal produce will always win on nutrient content over foods mass-produced and grown out of season. In addition I would recommend the following ‘supplements’:

- Organ meat, particularly liver, most days. Liver is the most nutrient dense food there is. If you can eat this lightly cooked so that it is still very red in the middle, then you will be wanting of very few nutrients.

- Bone broth or bone meal every day. Bone products are rich in haem iron, vitamins A and K, essential fatty acids, selenium, zinc and manganese.

- A fermented dairy food such as a full fat diary yoghurt or kefir. A good source of calcium and in a form that helps boost your gut biome.

- A good helping of oily fish every day. The best source of omega 3 fatty acids and the only source that is low in pro-inflammatory omega 6 fatty acids.

- Fermented or sprouted vegetable foods such as sauerkraut, kimchi or sprouted sunflower seeds. The fermenting and sprouting of these foods reduces the load of anti-nutrients contained in them.

In my next article I shall be provoking you to think again about the role of fibre in your diet. “Not a fibre of truth” will look at the somewhat shaky science that has made us obsessed with this component of our diet.